Plating the Twelve Months

An antique wooden box opens up to twelve little cabinets, each housing a plate carefully wrapped in white washi paper. Fingers slowly unravel the wrinkled paper amid rustling sounds, and an exquisite ceramic ware, roughly the size of one’s palm, appears before curious eyes.

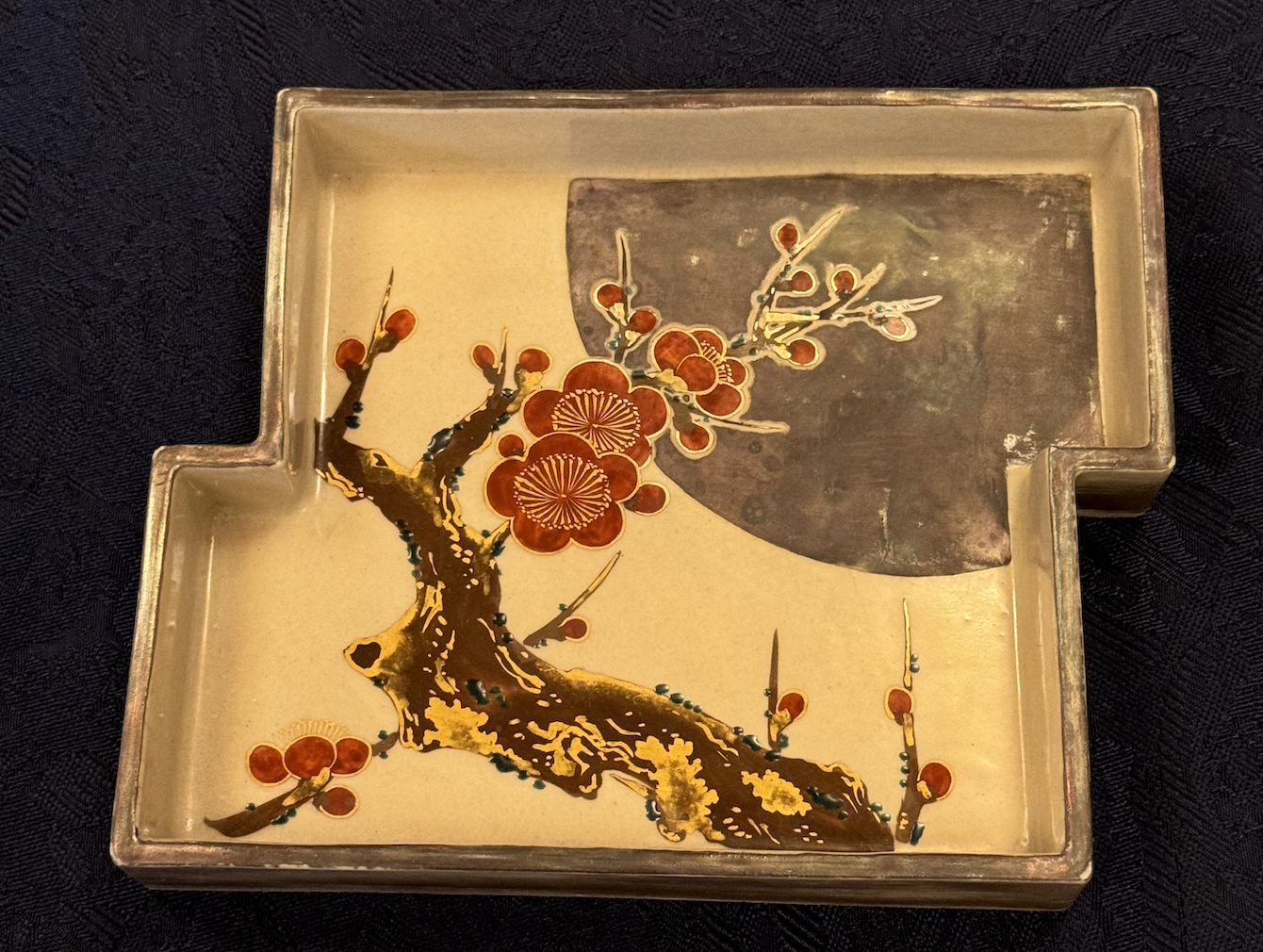

The plate is in an unusual shape, consisting of two joined rectangles that create a stepped, angular silhouette. Its surface is covered in a warm ivory glaze, over which lacquer-like motifs unfold in vivid underglaze colours. On this particular piece, two Japanese irises in deep purple and white stand elegantly against a soft, milky background. Each petal and gently folded leaf is outlined in gold, almost imitating stained glass panels with a sense of mysterious allure.

Holding the ceramic plate and feeling its rounded edges, the vessel’s texture is smooth yet slightly raised where pigments and gilding accumulate, catching light as the plate tilts.

What we have here, safely stored inside the wooden case and now exclusively viewed, is a complete set of ‘twelve months osara’ plates, made by the esteemed Ninn Sei family workshop with a 400-year history. Created for dining usage, especially in traditional kaiseki courses, the plates themselves were made over a century ago. Thus, every touch initiates a direct conversation with the past – craftsmen kneading clay and painting decorations under the roof, inspired by the respected nature.

At the core of Japanese cuisine lies a devotion to seasonality — nowhere is this more evident than in this set of twelve plates, each corresponding to a month, their motifs forming a visual calendar of nature’s cycles.

Putting down each vessel on the table gives a clear picture of how seasons are captured in visual terms. Due to their peculiar shapes, these wares seem to connect like a jigsaw puzzle, forming a long, continuous scroll or screen that matches all the natural cycles within a year.

For January and February, camellias bloom against gold brushstrokes, while two furry ducks swim across the slowly defrosting lake surface. A peacock leisurely walks underneath cherry blossoms in April, and a rich, red peony announces the start of summer in June. Chrysanthemum and maple leaves of varying colours and sizes occupy the dishes in the autumn and winter months, conjuring up a joyous scene of natural beauty even in the coldest days. All patterns, hand-painted in underglaze colours and fired in kilns, remain exuberant after a century, an eternal picture of the four seasons and high-quality craftsmanship.

These images, however, suggest more than a close observation and appreciation of nature. They also reflect the annual events in Japan, showcasing how pictorial delights, culinary traditions, and cultural activities blend seamlessly.

For instance, the April plate filled with soft white cherry blossom petals recalls the annual Cherry Blossom Festival, also known as Hanami, a word made up of Hana (’flower’) and mi (’viewing’). This is a significant event in Japanese society, where families would meet under the flourishing trees and enjoy picnics amid the ephemeral flowers. Shared bento boxes often feature fish cakes in pink and white, and hanami dango. Fairs and festivals also take place in gardens and parks, offering snacks and entertainment to the public. Everything seeks to emphasise the promising return of spring, and to relish the brief moment where the world seems to be covered in dainty petals.

Such attention to nature’s minute changes and the associated cycle of annual events is not limited to Japanese culture but widespread across East Asia – many terms and customs, such as dividing the year into 24 solar terms and linking each month to a flower, arrived in Japan via Chinese influence.

In China, the cult of the Twelve Flora and folk worship of flower deities developed during the Song dynasty (960-1279). The changing urban landscape in the Ming and Qing dynasties, prompting garden construction, further amplifies a correspondence between flowers and the months. Porcelain and vessels produced across these dynasties, like the Japanese set of plates, reveal innovative ways to capture this mythicised natural cycle in everyday wares.

The set of twelve Qing dynasty wine-cups in famille-verte decoration in the Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, now displayed at the British Museum, London, records seasonal literati sensibilities by incorporating monthly floral motifs and poetry onto drinking vessels. Compare the March plate from above and the February cup in this collection, one can clearly see similarities and cultural interactions. Around the delicate wine cup is a brown branch dotted with crimson apricot flowers, which signals the transition from winter to spring. The same image – especially in how the flowers are outlined and painted – is repeated inside the plate. Yet, the wine cup has additional lines of poetry inscribed on the side, which describe a scene with apricot blossoms, further reinforcing a connection between literary refinement and nature. Possibly used in wine ceremonies or in dialogue with scholars, the cup suggests a dynamic, sensory relationship between humans and seasonal delights, where eating and drinking become associated with time, a view that certainly influences the creation of the twelve plates.

Furthermore, both vessels demonstrate a deep understanding of the concept of ‘animism’ in Chinese philosophy. People had long believed that all natural elements are imbued with souls and personalities, hence the idea of Flora deities residing in flowers. This leads to the recognition of human decorum when living with nature, as one should treat flowers, trees, rivers and everything living in the same world with respect and care. Such a sense of order permeates the ceramic plates and porcelain cups, which corresponds well to the highly structured literary gatherings of Ming-Qing scholars, as well as the sequence of kaiseki meals.

From imperial seasonal month cups to Ninn Sei’s wooden crate full of historic plates, we could grasp how the culture of flowers travels across Asia, to be praised and encapsulated in food wares. Together, they embody a profound approach to co-existing with one’s environment, celebrating the twelve months through visual imagery, culinary practices, and philosophical nuances. In kaiseki courses, the twelve plates frame each bite with the rhythms of nature; circulated in literary gatherings, the wine cups enable scholars to commune with seasons through poetry and drinking. Savouring the fleeting and honouring the eternal, these wares narrate a tale of seasonal aesthetics across borders.